Teaching Indigo to do REST/POX: Part 9 (final part)

Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8

If you are in a hurry and all you want is the code, scroll down to the bottom. ;)

And for the few who are still reading: This is the 9th and final part of this series, which turned out to be a little bigger than planned. And if you read all parts up to here, you have meanwhile figured out that the extensions that I have presented here are not only about REST and POX but primarily a demonstration of how customizable Indigo is for your own needs. Indigo – Indigo was really a cool code-name. Just like many folks on the Indigo WCF team it’s a bit difficult for me to trade it for a clunky moniker like WCF, and it seems that this somewhat reflects public opinion. Much less am I inclined to really spell out “Windows Communication Foundation” in presentations, because that doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue like a poem, does it? But, hey, there’s always the namespace name and that doesn’t suck. “Service Model” is what everyone will be using in code. We don’t need three-letter acronyms, or do we?

But I digress. I’ve explained a complete set of extensions that outfit the service model with the ability to receive and respond to HTTP requests with arbitrary payloads and without SOAP envelopes and do so by dispatching to request handlers (method) by matching the request URI and the HTTP method against metadata that we stick on the methods using attributes.

And now I’ll show you the “Hello World!” for the extensions and about the simplest thing I can think of is a web server ;-) In fact, you already have the complete configuration file for this sample; I showed you that in Part 8.

Since things like “Hello World!” are supposed to be simple and it’s ok not to make that a full coverage test case, we start with the following, very plain contract:

|

[ServiceContract, HttpMethodOperationSelector] |

By now that should not need much explanation. The Get() method receives all HTTP GET requests on the URI suffix “/*” whereby “*” is a wildcard. In other words, all GET requests go to that method.

The implementation of the service is pretty simple. I am implementing it as a singleton service that is constructed passing a directory name (path).

The Get() implementation gets the URI of the incoming request from the To header of the message’s Headers collection. (Note that the HTTP transport maps the incoming request’s absolute URI to that header once the encoder has constructed the message.)

|

[ServiceBehavior(InstanceContextMode=InstanceContextMode.Single)] |

Once we’ve done a few checks on the URIs path portion, we construct a file path from the base directory and the URI path, check whether such a file exists, and if it does we create a message for that file and return it. If we can’t find the resulting file name, we construct a 404 “not found” error message. The UnknownMessage() method receives all requests with HTTP methods other than GET and appropriately returns a 501 “not implemented” message. Web server done.

Well, ok. The actual messages are constructed in a helper class PoxMessages that aids in constructing the most common reply messages. The class is part of the extension assembly code you can download and therefore I just quote the relevant methods that are used above. We’ll start with PoxMessages.CreateErrorMessage(), because that its very simple:

|

public static Message CreateErrorMessage(System.Net.HttpStatusCode code) |

We create a plain, empty service model Message, create an HttpResponseMessageProperty instance, set the StatusCode to the status code we want and add the property to the message. Return, done.

The PoxMessages.CreateFileReplyMessage() method is a bit more complex, because it, well, involves opening files. I am not showing you the exact overload that’s used in the above example but the one that’s being delegated to:

|

public static Message CreateFileReplyMessage(string fileName, long rangeOffset, long rangeLength, ReplyOptions options) |

The implementation will first make a guess for the file’s content-type based on the file-name, which is a simple registry lookup with a fallback to application/octet-stream. Then it’ll try to open the file using a FileStream object. If that works – ignoring the special case with rangeOffset/rangeLength being set – we delegate to the CreateRawReplyMessage() method:

|

public static Message CreateRawReplyMessage(Stream stm, string contentType, long rangeOffset, long rangeLength, long totalLength, string streamName, ReplyOptions options) |

That method takes the stream, wraps it in our PoxStreamedMessage, sets all desired HTTP headers on the HttpResponseMessageProperty, adds the property to the message and lastly adds the PoxEncoderMessageProperty indicating that we want the encoder to operate in raw binary mode. However, all these helper methods are already part of the library and therefore the application code doesn’t really have to deal with all of that anymore. You just construct the fitting message, stick the content into it and return it.

So now we have a service class and what’s left to do is to host it. For that we need a simple service host with a tiny little twist. Since the ServiceMetadataBehavior that typically gives you the WSDL file and the service information page would conflict with our direct interaction with HTTP, we need to switch it off. We do that by removing it from the list of behaviors before the service is initialized.

|

public class MyWebServerHost : ServiceHost |

The rest is just normal business for hosting and setting up a service model service in a console application. We read the first argument from the command-line and assume that’s a directory name. We verify that that is indeed so, construct the service host passing the singleton new’ed up with the directory name. We open the service host and we have the web server listening. The details for how the service is exposed on the network is the job of configuration and binding and, again, exhaustively explained in Part 8.

Below is the downloadable archive that contains two C# projects. Newtelligence.ServiceModelExtensions contains the extension set and LittleIndigoWebServer is the above demo app. The code complies and works with the WinFX November and December CTPs.

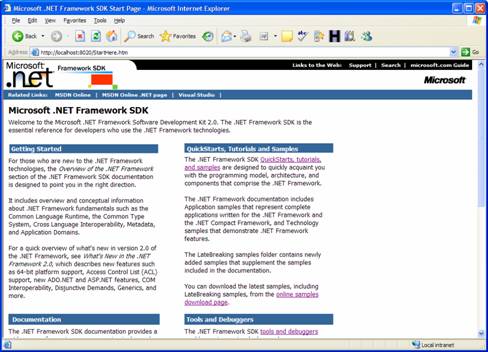

If you have installed Visual Studio on drive C: you should be able to run the sample immediately with F5, since the LittleIndigoWebServer project’s debugging settings pass the .NET SDK directory to the application on startup. So if you have that, start the server, and then browse http://localhost:8020/StartHere.htm you get this:

Otherwise, you can just start the server using any directory of your choosing, preferably one with HTML content.

And that’s it. I am happy that I’ve got all of the stuff out. This is probably the most documentation I’ve ever written in one stretch for some public giveaway infrastructure, but I am sure it’s worth it. I will follow up with more examples using these extensions. For instance I will show to use this for actual POX apps (the web server is just spitting out raw data, after all) using RSS, OPML and ASX. Stay tuned.

Oh, and … if you like this stuff I’d be happy about comments, questions, blog mentions and, first and foremost, public examples of other people using this stuff. License is BSD: Use as you like, risk is all yours, mention the creators. Enjoy.

Download: newtelligence-WCFExtensions-20060901.zip

[Note: I am preparing an update with client-side support and a few bugfixes right now. Should be available before or on 2006-01-16]